Learnings from early actions

By Sidney Hough, Mark Xu

January 7, 2026

Over the past 10 weeks, we ran weekly actions with a small number of members (30-50) to test and develop our basic organizational structures and processes. We completed 20 total actions.

In this time, we learned about factors that affect members’ reliability, built an understanding of how members experience the Alliance, and refined our process for action production.

Member reliability

The reliability of members is foundational to the Alliance. Among many benefits, reliability enables the office to make effective action plans because we know exactly how many people we can depend on to participate in those plans.

The first action that every member took on our platform was to sign our membership contract. The contract sets a formal expectation of reliability. This expectation is reinforced by other methods designed to build a general culture of reliability.

Members largely adhere to the contract. Only around 10% of people who signed the contract since we launched the platform have suspended their contract or had their contract suspended because they failed to complete their assigned tasks.

The membership contract imposes a barrier to joining the Alliance that deters some potential members. However, most people who signed up for the platform also signed the contract.

Other methods we employed to build a culture of reliability included:

- Sending automatic messages when members miss their deadlines. These messages helped some members better understand our expectations.

- Maintaining collective expectations by automatically suspending contracts when members miss too many deadlines. In other words, we define members to be those who keep their promises, which keeps action completion rates high. People whose contracts are suspended can re-sign their contract at any time. Some members reported being more motivated to complete tasks when they saw that actions had high completion rates.

- Creating smaller Alliance groups and assigning most new members to these groups. Group leads are in charge of holding their members accountable and send them reminders when necessary. Members report enjoying being part of groups and task completion rates are very high within groups, so we believe some evolution of groups will be core to future members’ reliability and experience of the Alliance.

Overall, task completion rates are 95% on average. Most non-completions come from new members who are unfamiliar with our expectations. We hope that action completion rates will increase as we strengthen our culture and the proportion of members who are familiar with our expectations increases.

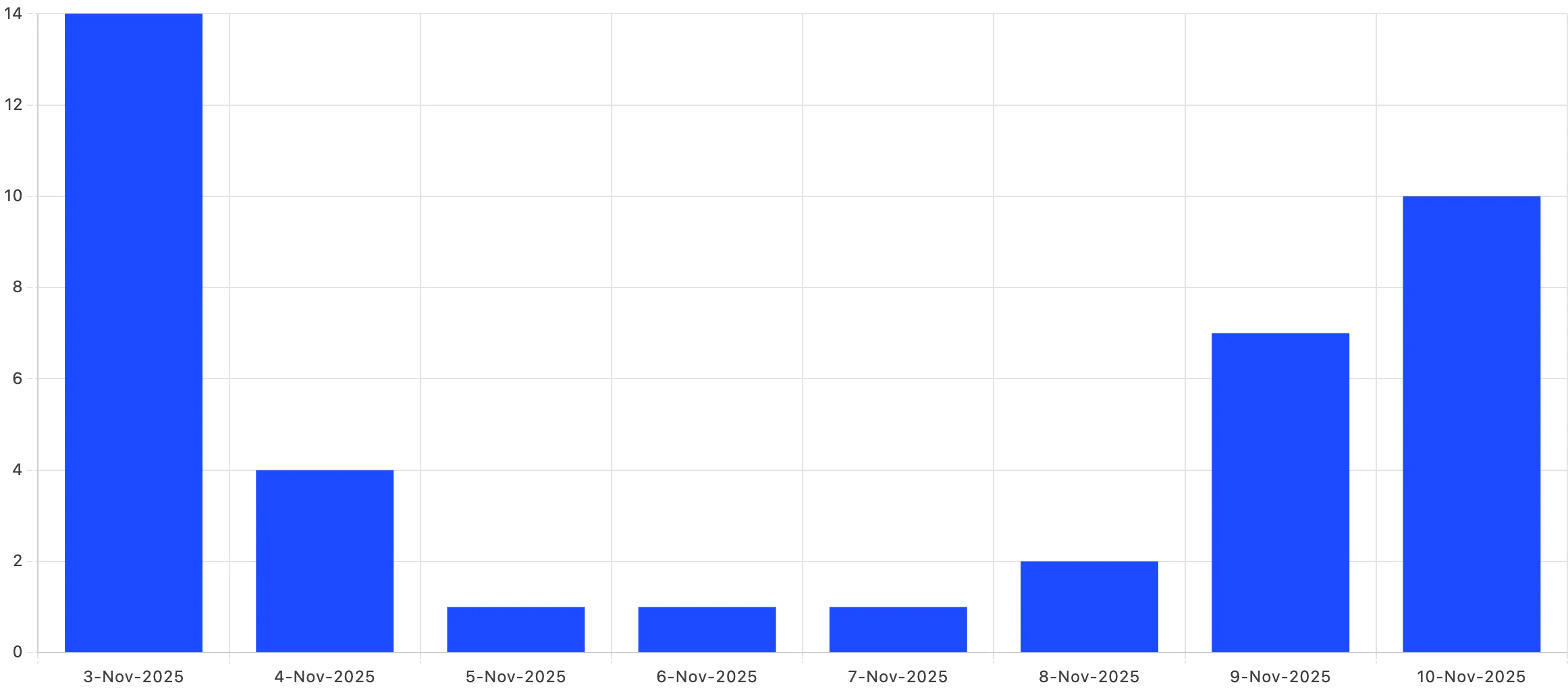

Task completions throughout the week for “Decide how to allocate $1,000 next week.” Typically, members complete tasks immediately or close to the deadline.

Task completions throughout the week for “Decide how to allocate $1,000 next week.” Typically, members complete tasks immediately or close to the deadline.

Member reliability has been enormously helpful in our current quest to properly set up the Alliance. If we need feedback, want to run an experiment, gather testimonials, announce new features, or interact with members in any way, all we have to do is launch an action.

Member experience

Working closely with early members has enabled us to improve how members encounter, understand, and experience the Alliance. While our primary goal at this stage is learning rather than growth in membership, we want to prepare our communications, processes, and platform so that they can accommodate future growth.

We now have 62 members. Early members were friends and family of Alliance staff. Later, we asked several Alliance members (especially group leads) to invite some of their own friends and family. A handful of members also joined the Alliance after learning about it through “Invite friends and family to fill out our AI privacy survey.”

In response to new members’ questions and comments, we took a number of steps to improve our invitations and communications. For example:

- We simplified our guide and moved more formal materials into separate documents.

- We combined our sign-up page with an invitation letter that provides basic information about the Alliance.

- We included examples of past actions on our website (and suggested that inviters include them in verbal descriptions), which help prospective members understand the Alliance much more efficiently.

- We gathered and answered frequently asked questions in a public FAQ.

We chose to tie growth to the smaller Alliance groups we mentioned above: we currently require group leads to approve member invitations. While we need a more scalable solution to group assignment in the future, this constraint has ensured that most new members are accountable to and assisted by an existing member.

Members largely enjoy our tasks and are willing to invite new members in the future. When we ran our first member oversight process in November, 94% of members believed that the vast majority of their future contributions would result in outcomes they approve of. The median willingness to invite new members was 8/10.

Members regularly expressed that they want more social opportunities. We plan to offer more opportunities for members to interact with each other on the platform, especially via groups and actions. We also intend to plan some virtual events for members who want to meet other members.

We also made many improvements to our online platform in response to requests from members. For example:

- We made certain portions of member task completions visible to other members.

- We added a messaging feature so that members and staff can communicate more easily about specific issues.

- We added a “progress” tracker to help members see the tasks they’ve been assigned.

- We added an information page so that members can easily locate Alliance resources and updates.

- We fixed many small functional and aesthetic issues.

Action production

Eventually, we hope that action production will be guided by subject matter experts and a long-term plan that addresses our priorities. For now, however, we develop actions opportunistically and with a focus on learning rather than direct impact.

We put great effort into designing actions that we think are worth the Alliance’s time. In the process of producing actions, we have found that there are nearly endless action possibilities and that the standards any particular action must meet are complex and difficult to satisfy.

There is not a one-size-fits-all approach to the design of particular actions. Often, however, concrete action plans develop around “seed” ideas. There are any number of “seed” ideas, many of which come from previous knowledge or random inspiration.

As we develop an idea into a concrete plan, we think extensively about additional ways to derive value from the action, including learning opportunities, new relationships, social opportunities, or increased impact on the world. For instance, we took an initial idea to help members adjust privacy settings as an opportunity to recruit new members and launch a media campaign. In another example, we took an initial idea to vote on donations as an opportunity to learn about members’ opinions on the need for consensus.

Ultimately, action plans must satisfy a complex set of criteria. Some of these criteria are hard constraints; for instance, the part of an action that requires member completion must take less than 15 minutes, and the justification for the action must accurately reflect the beliefs and priorities of the office. However, much of the difficulty of action design comes from a belief that we can, with effort, meet a wide number of additional desiderata, such as rapid turnaround of results, novelty for members, social opportunities, or use of concentrated (rather than distributed) member force.

More importantly, at this stage, we want each action to test a specific hypothesis so that we can derive unique learning value. For instance:

- In “Sign a letter requesting news coverage of a bring-your-own-cup cafe coalition” we learned that some businesses will make policy changes in exchange for assistance in acquiring media coverage.

- In “Answer questions about nonprofit website copy and design” we learned that we can begin to build relationships with potential future partners by providing small-scale help.

- In “Participate in an experiment to measure AI + follow-up friends and family campaign” we learned that Alliance members spend greater effort completing actions than external participants.

We have also paid attention to the diversity and coherence of our full action sequence. We wanted actions to balance with and build on one another. For example, in “Decide how to allocate $1,000 next week,” many members suggested that we donate to GiveDirectly, a non-profit they learned about in “Read and discuss an article about global inequality.”

Other updates

The legal entity we use to manage funds and pay members of the office was approved as a U.S. 501(c)(3) non-profit organization.

The office has 5 staff members now. We expect to hire 2 more staff members in early 2026. These staff members develop action plans and our online platform.

We now have a physical office in San Francisco, California, U.S.A.